Hey y’all,

It’s been a long, busy absence on my end. Apologies, but it should pay some cool dividends for this space soon. (Cough!— Comics!— Cough!)

Speaking of this space— you may have noticed that from time to time, this is where I like to rough out topics for potential DRAWL episodes. So how about I stop preambling and get to that? ‘Cause it’s a big ‘un today….

Like many of you, I was surprised to learn that the masters of time who presently bend and warp what we like to call reality have seen it fit to place the release of MAD MAX: FURY ROAD a staggering 9 YEARS in our past.

Which means that there has been nearly a decade to build the hype and excitement for a movie that did not seem to need the extra juice—

FURY ROAD’S prequel, FURIOSA.

But as that moment finally came for FURIOSA to roar and rage— its ad campaign seemed to instead sluggishly lurch in from the barrens— sun stroked and slow-footed and oh so overly thirsty to capitalize on what the studio *thought* we wanted to see next.

And so earned or not, those early FURIOSA trailers shouldered the weight accumulated by all of the previous prequels and IP renewals that have been trotted out to sell us new/old rope. Of the deferred fatigue of superhero cinema. And just maybe of one too many run-ins with real-world apocalypses.

In trailer form, FURIOSA’S once riveting aesthetic felt borrowed and repetitious. An absolute whiff at a meaty pitch down the middle of the plate. My expectations sank to anti-nothing. I thought it was gonna stink.

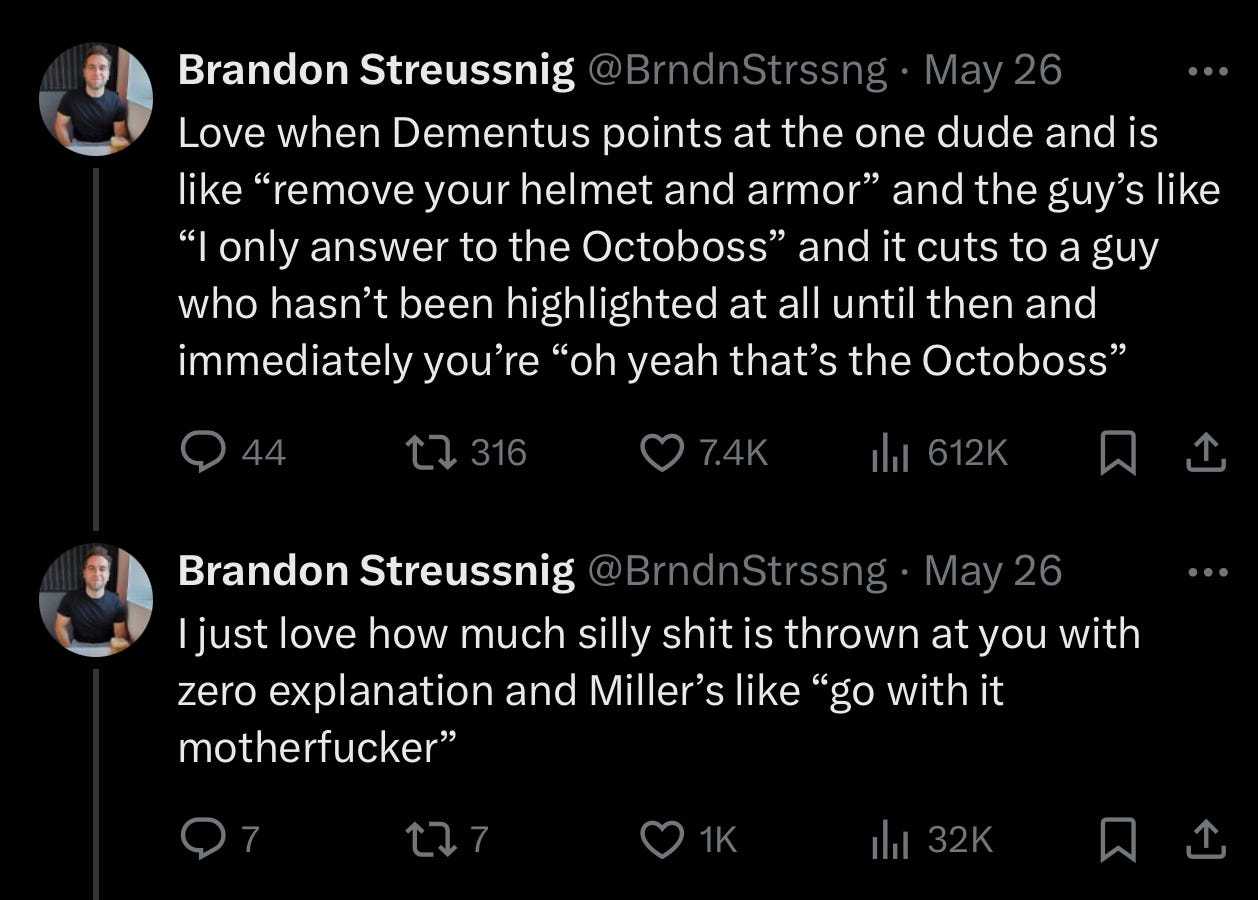

But as I discussed that feeling with friends who read it the same way— something weird started to happen. Okay, it’s not weird if you know me AT ALL—but the more we bashed what was being sold to us, the more I started to question why.

I mean, film marketing and filmmaking are two VERY different, arguably often unrelated, things. So why was I acting like George Miller’s creative vision— which had delivered its highest point with his last outing— had done anything to earn my apathy?

Determined to further convince myself that I am indeed an overly opinionated asshole, I decided to revisit The Mad Max films in order.

Hoping all the while that the momentum of the franchise would carry me safely across the wasteland and that in the end, I would arrive in the theater all shiny and chrome, and at last eager to witness the first (and latest) ride of FURIOSA.

And guess what? In the end?

That happened.

I loved the movie.

But what I loved more was the moto-murder movie marathon that lead me there…

MAD MAX is a “film franchise” (or more accurately a story) whose production spans 44 years.

Initially breathed to life as a guerilla indie film. One chiefly spearheaded by a fresh-faced, young doctor who left the emergency rooms of Australia in the hopes of crafting a drama about the road violence he’d witnessed there.

But when the expectations of realism wouldn’t or couldn’t hold the emotional and imaginative tenor of his story, George Miller did what all the greats do—

Threw up his hands and said, “Fuck it. It’s set in the future”.

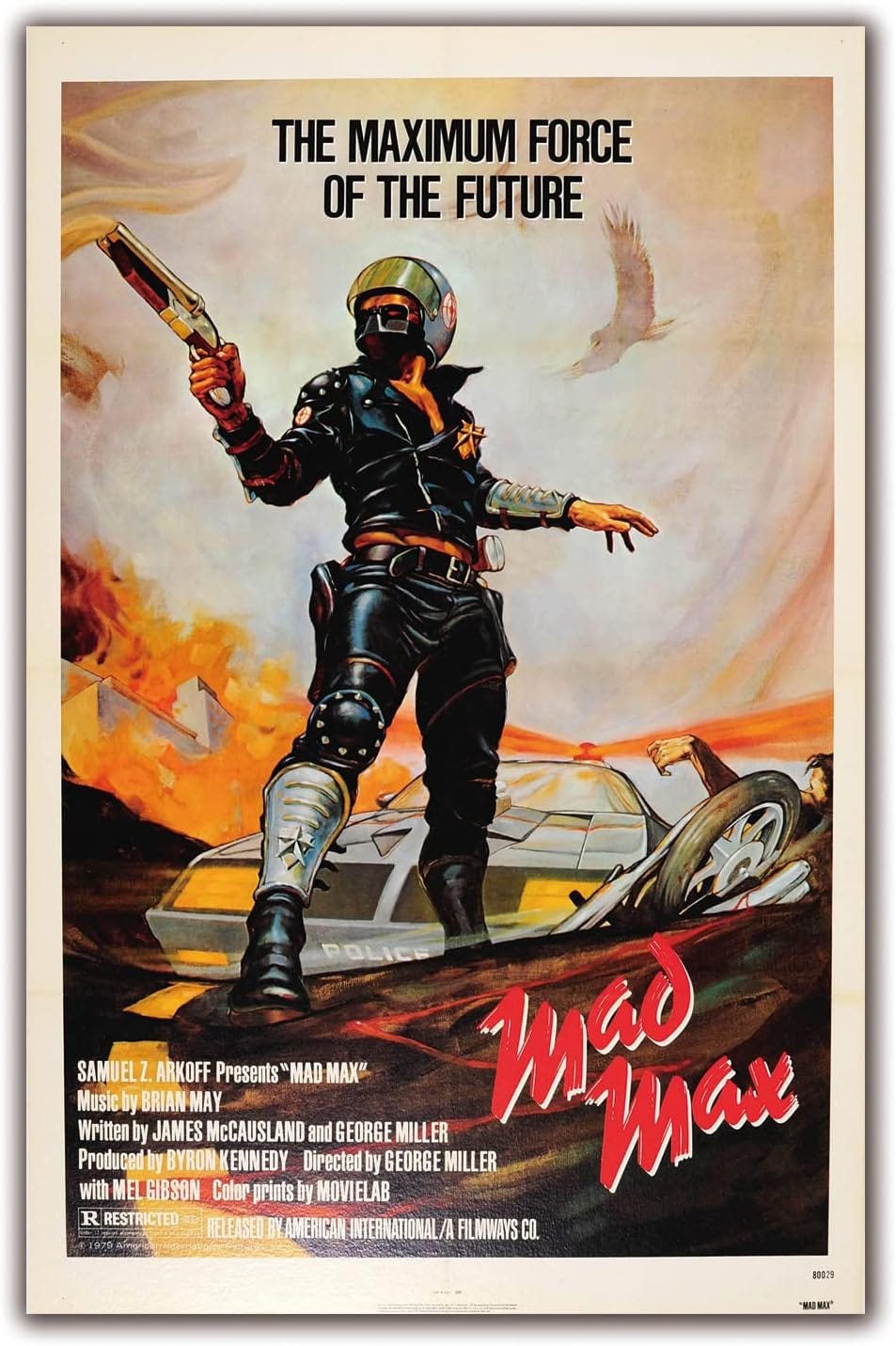

And indeed that first movie (MAD MAX, 1979) is pretty fucking wooly and wild as a result. A brilliantly flawed, clunky, and propulsive piece of high/low art.

If it is like anything, it is perhaps most superficially like A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, filtered through a 2000 A.D. comic strip, on both literal and chemical speed. Full of car chases and crashes that are almost uncomfortably real—It’s made with the bluster and immediacy of filmmakers and stunt folks who probably didn’t know exactly what they were doing, or making, or why.

A western on pavement, MAD MAX is ostensibly about the highway patrol on the thin edges of a crumbling society.

When there are no norms anymore more— who maintains them? Why?

And what are the consequences of choosing to face that chaos?

In that first film those themes, were at best loosely illustrated. And by Miller’s admission the sequel, THE ROAD WARRIOR (1981), takes note of all the things critics seemed to love or see hiding in the edges of his film and leans into them.

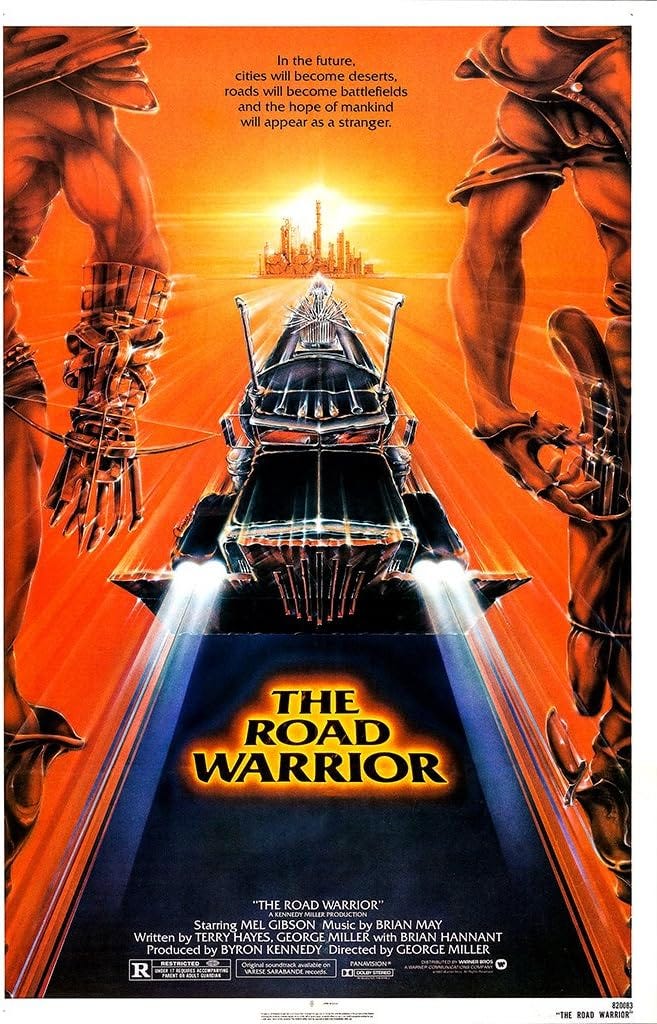

As The Road Warrior, Max becomes is a starker, bleaker, almost fatally calloused survivor. An confused tangle of contrition, penance, and self-flagellation, hidden only by a stiff upper lip and held together by G-force stressed leather.

This time out Miller deftly inverts Noir-ish and Western tropes of would-be lawmen in lawless lands. But more importantly— uses Max’s transformation to spur his descent into the harsher, more unhinged depths of the franchise’s true star— The Wasteland.

Where the first film’s near apocalypse hand waves the concerns of the real world away— its sequel creates its own. A commitment to world-building so secure in its unspoken, internal logic that it allows the audience to be tossed into its deep end without much care, or cause, or need for explanation.

As a result, ROAD WARRIOR moves like a hunted, hungry animal. Each step of the story seemingly governed exclusively by a singular need—

Survival, at all costs.

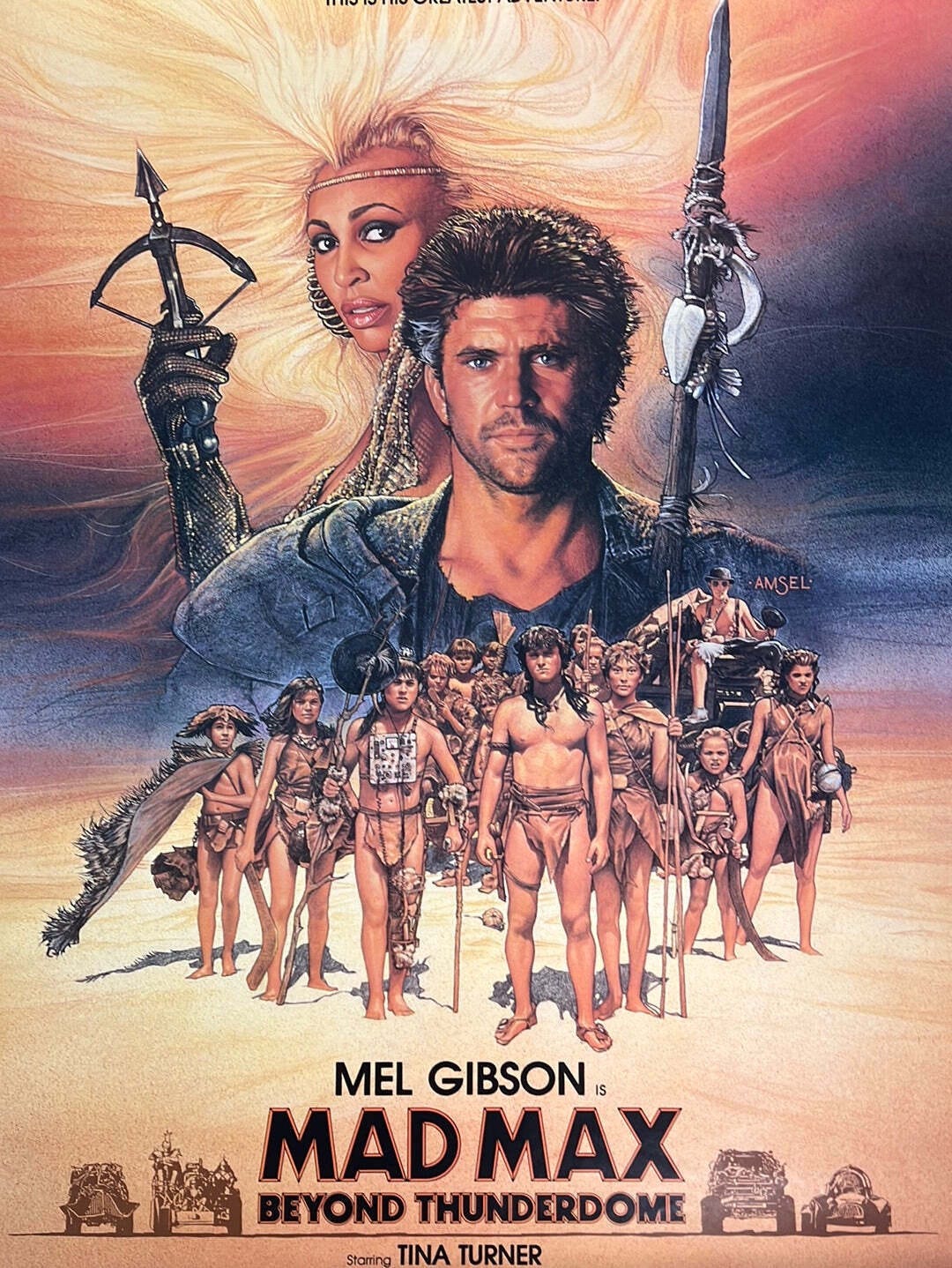

But for all the sequel’s sun-fueled superpower, MAD MAX: BEYOND THUNDERDOME (1985) surely underscores the reasons why kryptonite and cash are both green.

Despite the spectacle and sound bytes* that make it a true gem of a cultural artifact, THUNDERDOME is overall (especially in the back half) a bloated mess of a movie.

Too saccharine. Too hand-holdy. Too studio-y. THUNDERDOME is a spiked leather biker daddy trying to blend in with the khaki pants at his kid’s school’s first PTA meeting. It just wants so badly to be liked by people who could never, ever truly love it.

But the most pointed irony of the complete and utter compromise that is THUNDERDOME may lie in its setting.

“Who runs Bartertown?”, a question Miller and company may have been asking themselves more than anyone else.

Despite my feelings on THUNDERDOME’S stumbles— With it, Miller had what seemed like the last hammer strike in forging his three uniquely weird, and borderline reckless films into the shape of a ramshackle franchise.

A vision impactful enough that it set the tone and aesthetic for a seemingly un-killable sub-genre of derivative post-apocalyptic fiction. A glimpse of the future so plausibly and practically within reach that it lives on in every B movie with the budget for a muscle car and a set of spiked shoulder pads.

A cultural relevance that, while still likely thousands of miles away from what George Lucas saw with Star Wars— might still have been sci fi’s last, best chance for gas on the long desolate stretch of DIY filmmaking highway that was the 1980s.

A staying power made more implausibly absurd, considering that the only sure thing George Miller seemed to know at the start of making these movies—

Was that he NEEDED to make these movies.

And yet the act became so completely transformative— that no matter how much filmmaking has changed over that 4 decades long span — the lessons learned along the way remain fused at the core of both filmmaker and franchise.

On one hand, MAD MAX: FURY ROAD (2015), and FURIOSA: A MAD MAX SAGA (2024) are sweaty, flailing, physical films that careen and swerve with the same reckless abandon as the hordes of ROAD WARRIOR era stunt drivers.

On the other, they are Rube-Goldberg machines of considered, conscious, laborious, storytelling. Meticulously storyboarded** and rehearsed. The kind of filmmaking that torques the computer into a greasy power tool. They refuse to simply take what technology gives, and instead harness it to craft what MUST be.

The world-building Miller leaned on in the past is taken to its ultimate, animation-informed conclusion. As each character and environment is designed and designed again. Only to then be confidently discarded or truncated as the story dictates.

EACH FRAME is considered and invested in— but ultimately weighed and judged.

Life or death stakes, that not only echo these films underlying themes elegantly but underscore what drives them— A collision between the order of planning and the chaos of actually doing.

A propulsive tension. An atomic fusion that only occurs when what you KNOW grinds against what you SEEK.

And I don’t know about you, but for me, standing here staring out at this cold, sterile age of AI and algorithms?

This approach is the church, the choir, and the whole damn Tabernacle.

As close to the blueprint as there currently is for how to not only survive, but thrive in the cursed artistic ruin to (possibly) come.

Gifted to us by the little oddball, outsider action films that could. Films that, despite their main drive to ooo and ahhh and vroom, vroom— are stellar examples of the elasticity of an artistic vision. Examples of why it takes messy, flawed and hungry humans to explore the intersection of where we start and our world stops. No matter how chaotic or alien that place seems to become.

The only kinds of stories that can and will grow with the audience.

Because they grew alongside the creators who dreamt them up in the first place.

When there are no norms anymore more—

Who maintains them?

Why?

And what are the consequences?

LINER NOTES:

*Tina Turner in particular is pretty spectacularly over the top, both in the movie and on its soundtrack, for which she cuts not one but TWO great yet absurdly theatrical singles. Not knowing the story behind her casting I gotta believe she either loved ROAD WARRIOR,— OR— loved THE ROAD WARRIORS, and possibly signed on thinking she was going to get to wrestle those maniacs. Either way she rules.

** For the initial gestation of FURY ROAD, those storyboards served as an over 3,500 frame first draft of the script. A process that took YEARS and heavily involved comics artists like Brendan McCarthy (who also co-wrote FURY ROAD), and Mark Sexton.

Though there are tons of comic artists who cross over to film or animation and back, the degree to which Miller credits and respectfully names his collaborators so specifically as comic book artists is a strangely atypical thing. Sincerity aside, I think it speaks volumes about his ability to fit all that information into the lean, mean, nearly wordless reality his later films inhabit.

I feel compelled to add that by no means do I think I’m an expert on George Miller or these films. But the often messy, unorthodox histories and methods behind these movies are a growing curiosity of mine. For a better look into Miller’s modern take, especially as it applies to my editorialization, I highly recommend the full NEW YORKER INTERVIEW.

Here’s some snippets I got a lot out of:

On the fragility, malleability, and necessity of a POV.

On his wife and editor Margaret Sixel’s sizable contributions to his process.

That’s all for now. Hope y’all have a great weekend.

More very soon…

-j

Oof. Apparently I was a year off on the date for FURY ROAD. It came out in 2015. Editing that now, but just wanted make a note of the mistake so that y'all to feel that extra year too.

Oh man. I saw first Mad Max on an indie over-the-station on a late Saturday night when I was 13 or 14. Still my favorite of the series.