08/23/24: WHEN WRITING IS DRAWING

And when movies are comics.

Hey y’all,

It’s been kind of a heavy administrative week around my way. So, I’m going to skip today’s BIG SHOES post and aim for a decent update next week.

But since we’re all here… I might as well keep the momentum this space has seen this summer and discuss a little train of thought I stumbled on while recently re-visiting the ALIEN franchise. (See fan art below and throughout.)

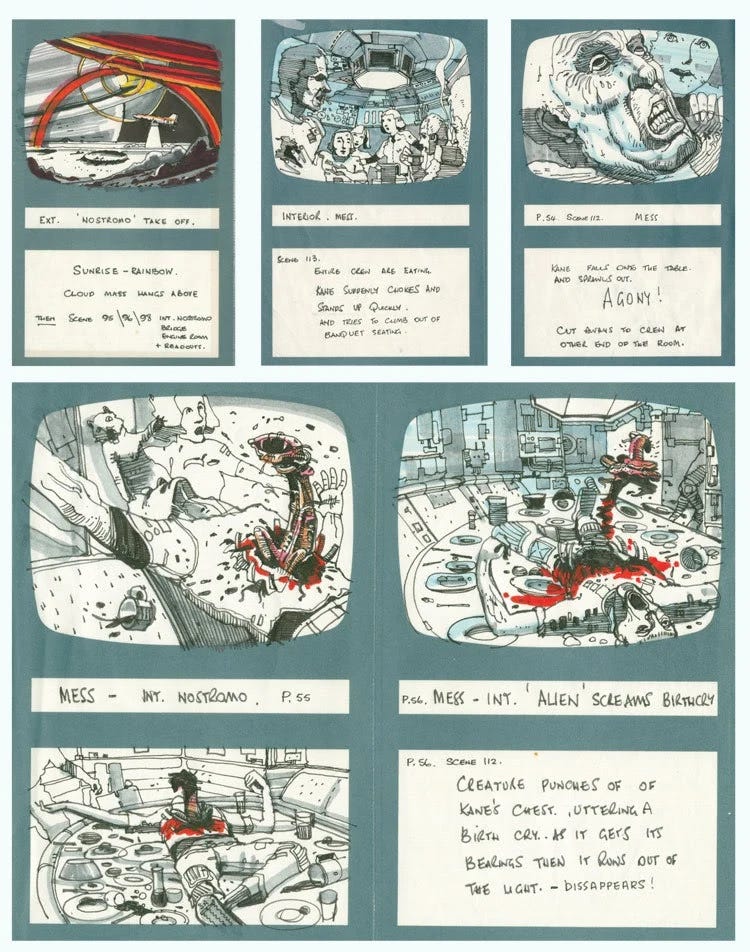

In the scuttled preparation for an intended entry about said Xenomorphia— a MAKING OF ALIEN documentary lead to the (re)discovery that not only did Ridley Scott direct the first ALIEN, but he also storyboarded it.

And boy did he storyboard it:

Man, no disrespect to Sir Ridley, but there’s a level of care and expression in these boards that honestly surprised me. At least in part, because modern storyboards are (in very broad terms) produced under such duress and time-sensitive conditions that they don’t often feel like the person making them has impetus or incentive to care that much about aesthetics.

With the speed of digital filmmaking, a visually literate sequence is more and more considered someone else’s job. Or something to be solved on set. Which is part of why you see so many talking heads in TV shows and superhero movies. They’re cutting corners where they can. Because you best believe the special effects-driven action is “boarded” in some way, shape, or form. It has to be. It’s basically animation.

But as I’ve said MANY, MANY, MANY times… drawing (for stories) is mostly, or at least primarily, about communication. Many times aesthetics are a part of that communication. And with a film as intricately designed, imagined, and literally BUILT as ALIEN— it makes a ton of sense that the storyboards would be equally labored over and loved on.

RIDLEY SCOTT: I was steeped in Heavy Metal comics(…) Métal Hurlant s(…) and you know a lot of Moebius’s stuff actually.*

And I was very impressed by that, and in those days kind of wondering, how do I apply this to movies you know? How do I apply this kind of really fresh and beautifully visual thinking to film? And here it was.

You need a hook when you’re starting something, and my hook was my boards. I drew the boards. Drew the corridors. Drew the space suits. When you're drawing boards and corridors and spacesuits, you’re also sucking yourself into the story, because I'm literally doing it, you know, chapter by chapter. Scene by Scene.

You get ideas as you're drawing them. And the ideas fall into place not just as ideas but as technically logical possibilities(…)

It’s like writing. The boards are like writing.

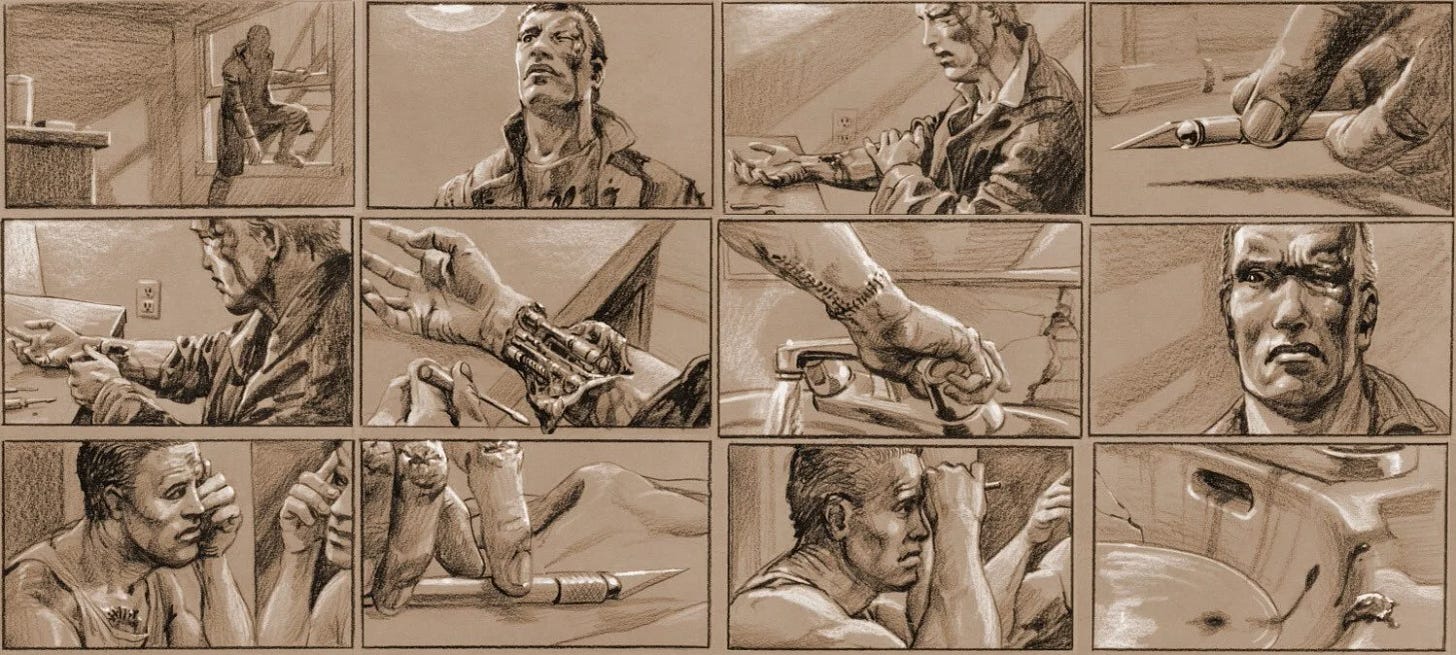

And if you think Ridley Scott cared about his storyboards, then shake the flesh-gloved cybernetic drawing hand of ALIENS writer/director, and TERMINATOR writer/director/storyboard artist, JAMES CAMERON:

JAMES CAMERON: Cinema is a feedback loop between the art and the storytelling.

I didn’t, you know, I thought maybe I’ll write a novel and I’ll illustrate it. And that didn’t exist. I mean they had comic books, but they didn’t have graphic novels yet**. But that was my idea, that’s what I thought I was going to do.

I was thinking in panels, I was thinking in frames. So I was really thinking in shots, if you think about it. So the transition into filmmaking was really pretty easy. Because it was just an extension of everything I’d been doing.

And now just for fun/a modern perspective, here’s something I heard director Denis Villeneuve say about making DUNE 2:

DENIS VILLENEUVE: I will say what is maybe more specific to my approach is the storyboards, where I will draw (along with my storyboard artist) the whole movie.

That helped me tremendously to dig in. To sculpt the movie. To find the voice, the cinematic vocabulary. To apply that vocabulary to the old structure. To create props, costumes, vehicles. Not thinking that I will necessarily come with THE idea. But at least that I will find ideas to feed my crew later. And there’s a lot of things that are ideas that are coming out of this.

And more importantly the idea of the Mise-en-scène. Where I will very often find the proper way to shoot. And going through the words to the image there’s always a certain amount of serious transformation that goes into the process where I will go from the storyboards and rewrite the screenplay after from the storyboards (… ) that’s where I feel really the movie is born.

My point here is—that in a visual medium, the writing is very often in the drawing. And even when it’s not, the words and images are in a dead heat sprint toward your eyes.***

As such, the above quotes apply to my process on pretty much every comic I’ve ever drawn. And though I have often leaned on the drawing mileage under my belt when scripting for others— I do regret not doing layouts (aka storyboards) on many of those comics first. Often I avoided doing so simply because I didn't want to hamper the art team's creativity, or insult anyone with even the whiff of the suggestion that my take was better, (I *try* to live by the maxim that if I think I could’ve done better I should’ve drawn it). Though mostly, chiefly, it was because the ridiculously archaic pace and machinery of work-for-hire comics tends to discourage that type of bread-breaking back and forth.

But in live-action films, with literal armies in collaboration, the practical benefits of “dreaming on paper”, as Villeneuve put it, go hand in hand with loftier artistic goals. And though they are far cheaper and “easier” to produce, there are many, many reasons why you should incorporate storyboards into the writing of comics. In fact far too many to go into today.

But here’s one:

With no sound, or actors, or motion—the audience in comics is the first and final filter. They are actively, and likely privately, bringing their imagination to bear in order to interpret the story. Meaning the creative team should at the very least see if they believe their story works as a comic— as words AND images on a page— before sending it out to the rest of the world. A lot of times you just simply cannot tell if a something works before it is SEEN.

To me, the feed back loop between all your planning and the live fire of execution that is created by writing and drawing a comic is the biggest commonality they have with filmmaking. (To make a comic is to draft perfect plans on a sunny day, only to do construction in a hurricane.) But if you don't buy it, or you don’t like the work of the filmmakers I’ve referenced above, there are countless examples of others who use a similar, or even more elaborate process.****

That is not to say that comics should try to emulate the precision required to command the Roman legions of a film. The freedom from a ticking clock surely allows for a beautiful comics illustration to exist for the sake of a beautiful comics illustration. There’s space on those pages for experimental stream-of-consciousness or abstract story sensibilities to be mulled over or meditated on. There is definitely a unique freedom and power that comes with just putting someone’s strange take on a little paper stage. To be considered for as long, and from as many angles, as the reader (or creator) has the interest to do so.

But if you’re trying to communicate a visual narrative beyond, or different than, those conceits. Or you’re a writer struggling to nail down either end of the micro/macro scale of your story, I would advise at least trying to build it holistically. From drawing it frame by frame. Because though words are truly incredible in and of themselves—

Even a few bad drawings tend to make comics better.

LINER NOTES:

*There are a lot of weird overlaps with comics and that first ALIEN. Screenwriter Dan O’Bannon actually even came up with the idea for the movie shortly before meeting Möebius in pre-production for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s scrapped DUNE film. An experience that directly influenced ALIEN’s visual conception.

** Massive respect to Jim Cameron but— (and I know he’s just riffing, but)— my eyes are rolling down the street at his “oh they had comics, but didn’t have graphic novels” grandstanding.

***Psst— words are made of letters and letters are drawn. In fact, you draw every time you write something by hand. I promise.

****I’ve spoken before about how the sequencing style of storyboarding used in animation like the SPIDER-VERSE films is of great benefit to comics. READ THOSE THOUGHTS HERE.

Alright, that's it for this time. Hope y'all have a great weekend. As always, thanks for your patronage, and your patience.

More soon...

-j

Another fascinating piece; there's probably a book in the subject (if there isn't already one). Scott's storyboards for all his flicks are famous; they're know as 'Ridleygrams', he went to art college before he transitioned into film-making (through advertising). Same with James Cameron who didn't 'just' do Storyboards; he did the actual 'Rose sketch' for Titanic and IIRC the first Avatar promo art (close up illustration of Navi eye). The link between Comic narrative and storyboards is massive; look at all the comic artists who work between the 2; Steranko on 'Raiders', Jock on 'Batman & Dredd', Fegredo on 'Noah', Chris Weston on multiple projects. And that's without even looking at the Comic Artists who also do concepts; like yourself, McCarthy, Weston, Glyn Dillon, Guy Davis. Make sure you check out 'MEZOLITH'; 2 volumes of stunning comics by Adam Brockbank who's primarily a film concept artist.

Alien 3 is (kinda, almost) the shit.